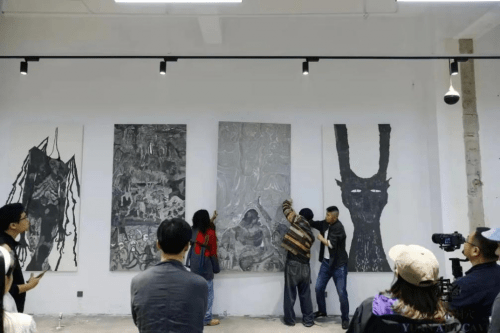

赵明远“远艺术洞穴”在杭州开馆,“空生大有”的艺术狂想

“Form does not differ from emptiness; emptiness does not differ from form. Form itself is emptiness; emptiness itself is form”.

Art begins always with emptinesss, an empty space, a blank canvas, a white paper. A flat mental white wall confronting the eyes, body, mind and hands of the artist. A void with a meaning, a state of virginity, in waiting, with a potential promise. Whatever tool used, a brush, a pencil, a piece of charcoal, a knife, ink, water or oil, with all its differences, the white mind wall is always what needs to be overcome. Its virgin-like surface carries a promise of a future and a possibility of change, a new becoming. Not as an obstacle but as an entrance to something else, to an invisible spatial universe where imagination and action forms and transforms a vision into seeing and being, into humanity. As a site of meaning.

When Yves Klein on April 28 1958 opened his exhibition Le Vide it was as an act of extreme iconoclasm. With the courage of a pioneer he decided to exhibit the unexhibitable, pure emptiness, a void space, an emptied Galerie Iris Clert, enlightened only on the opening by a soft bluish light. No objects, no art works, nothing was on display. Except a void which when filled with visitors naturally transformed it into a site of being, as an embodiment of Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism in Being and Nothingness (1943). It was a radical act, relating to Buddhism, Daoism and Zen, with the profound philosophical reference for which void is a blank signifier of meaning. But also a reference to a contemporary situation in lack of mind and spirit, as a critique of a material consumerism. A point which Klein’s friend Arman made clear two years in doing, Le Plein, (The Full), filling the same gallery from floor to ceiling with garbage found on the street, making it impossible for anyone to enter. Yves Klein’s The Void was a radical act and event of groundbreaking dimensions, a mind divider, and perhaps the first conceptual art work with as profound theoretical ramifications as Marcel Duchamp’s readymade urinal, Fountain, rejected by the Jury of the Independent Salon in New York in 1917.

A similar concept inaugurates Yuan Underground first official opening, a void, an emptiness, as a starting process of a work in progress. Its nothingness corresponds philosophically to the notion of the unique visual style in Chinese painting known as the intended blank, a blank space which directs the viewers experience of contrast between emptiness and solid form. Used as a way to emphasize the value of silence, following Laozi’s concept which John Cage embodied in his famous silent composition 4′33″, that “the great music is without sound, the great form is without shape”. Intended blank, simply called “blank” or more poetically “the remaining jade”, is furthermore used as a tool to open up the beholder’s unlimited imagination. As a fresh starting point and an instrument of perception psychology that functions like a visual trigger and mind-opener, to stimulate optical participation. Its its essence is impregnated by Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism, and finds a powerful articulation in the intended blank. Formulated in thePrajñāpāramitā-hrdhaya or Buddhist Heart sutra as : “Form does not differ from emptiness; emptiness does not differ from form. Form itself is emptiness; emptiness itself is form”. Or as Laozi put it in his Dao De Jing : “everything on earth is born of Being, but Being is born of the nothingness of Dao”.

The symbolic act to open the Yuan Underground with an empty white space, like a blank sheet of paper, to showcase a process, signifies a courage and intention. That art is all about change and progress, but also of a new conceptual beginning. That just like life, art is a process, starting from the spatial void of nothingness, which slowly and over time will be filled with ideas, thoughts, emotions and vision in the form of paintings, assemblages and sculptures. It relates as such to both Chinese philosophy, Western existentialism as to Yves Klein zen-based conceptualism. But also to the thoughts of Joseph Beuys who claimed that the exhibition itself was an art work, a vital process of artistic practice, inspired by the form used by James Joyce when writing and publishing his modern masterpiece, Finnegans’ Wake, as a series of separate essays declared as a work in progress.

The criteria of value of art has certainly changed over the centuries and millenias, the contemporary currency and meaning of traditional landscape painting is not the same as it was two hundred years ago, nor does contemporary art today has much to do with how it appeared 1923. Even if we today still can look back at Cubism, Fauvism, Dada and Surrealism with admiration and inspiration for how they transformed our way of seeing. Or for that matter how the 1985 movement in China with its engagement and passion for an art of the avant-garde, profoundly pushed the limits of mainstream society. Finding forms with new ideas, subjects informed with new sentiment, and above all formulating the tradition of a new conceptual China from Xu Bing to Zhang Xiaogang, from Xiao Lu to Shen Yuan. Articulating the iconoclastic intelligence and depth of Chinese contemporary art, at times conscious at times intuitive and emotional, but always aware of being part of a larger and historic artistic discussion.

Today the situation is different. What we have is what we miss. There is of course artists from a younger generation that is truly original and of great interest, but most still need to confirm themselves. They need to stand up for something, to stand out, or even perhaps against something. They need to be artistically courageous, to be young, as only young artists can be. It is not about rebellion or provocation, but about finding new forms and not to conform oneself to the mainstream. To truly understand the meaning of the tradition of the new, to study and learn from artists in recent history, as to know what not to do and what originality honestly signifies. To envision the groundbreaking, but also simply to be young. This is where young Chinese art stands today, at a crossroads of being young or entering an early decorative retirement in the market’s colourful darkness.

It is in this context we have to consider the work of the young artist Zhao Mingyuan, but also his attitude. He is different, he says what he believes and do what he likes. He believes with passion that art is a medium of truth, a non-conformist way of expression, a field of individual freedom, which made him decide to quit school when he felt that the classroom closed his mind, that it formated his free will and creativity, his thinking and mindset. One day when all the students were assigned to paint traditional landscapes, Zhao Ming Yuan began to paint a boney street dog that was looking for something to eat in the garbage outside the school. It was in a poor state, unhealthy, and Zhao Ming Yuan empathic mind made him chose it as his subject. One of his teachers who had always been there for him was supportive, but another reacted vehemently against it, which provoked Zhao Ming Yuan paint the dog over and over again in a multitude of ways. Insisting on its validity.

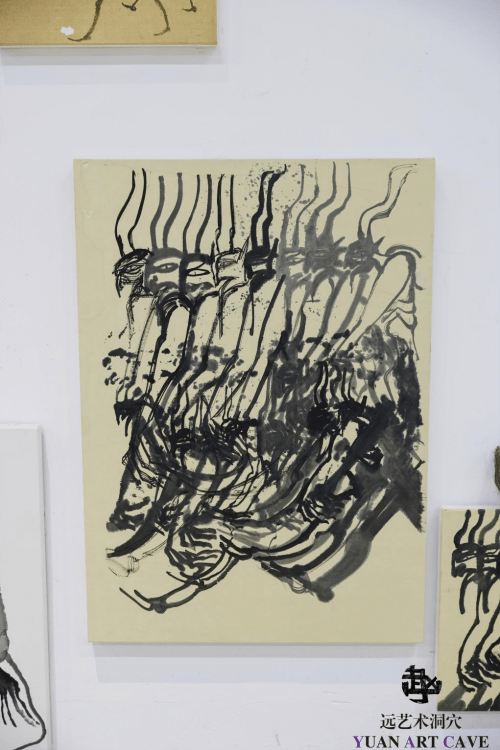

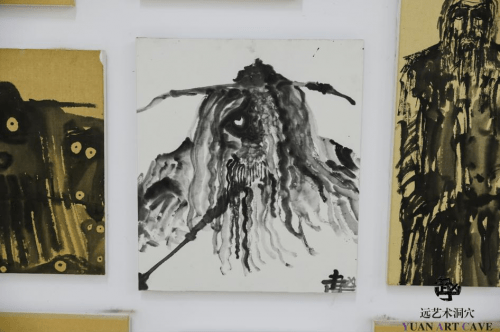

He then introduced a second motif, that of a beggar, making the beggar and the dog symbols of his own independence, painting them in class, in front of the teacher, while his classmates followed the directives to paint or copy the assigned classical landscapes and dead stuffed birds. Where are we ? is the question we can ask when we see these pictures. What is that for a kind of dog that at times resembles a calligraphic character, at times an impressionist blur of strokes in movement, or a visage looking at us with two large eyes. Why is it there and what is its signification ? In one fine lined drawing the dog is even wearing the same large brim hat as the beggar, as a metamorphosis of the two motifs, signaling a proximity in meaning, a double identification. Articulating a both simple and complex relationship.

The beggar in its turn is repeatedly represented with only one eye, a large brim hat and a long pipe, attires and attributes, that puts the motif in a logic time zone of ancient mythology. Both the dog and the beggar appears most of the time in solitude against a blank white background. Yet in one large-scale painting we see the beggar together with a group of other figures, of which one distinctly stands out with the face of a death skull, wearing a long dark coat and a soldiers cap. Giving a direction for the interpretation of both the beggar and the dog.

Obviously, the subject at hand is not only a dog, the beggar not only a beggar. They speak about something else and while articulating a certain sadness and sense of being lost, signify as Zhao Ming Yuan attests, a freedom to live and do as they want. We understand that these are existential figures, distinct psychological and personal signifiers. Not only representing freedom from the imposed and assigned idea of art as production, and the artist as a producer on demand. But also symbols of independence, of a rejected and disliked subject matter, a poor man and a poor animal.

Beyond the particular and personal symbolism inherent in these pictures, it is difficult not to consider the motifs traditional meaning as popular signifiers. In particular when knowing that the dog is the oldest domestic animal in China, used for 25,000 years for both protection and companionship. It is loyal and honest and constitutes as we all know the eleventh of the twelve animals in the zodiac, arriving next to last in the Great Race set up by the Jade Emperor to name and order the calendar years, just because it prefered to play in the river instead of competing. The dog is an important and loved motif in Chinese mythology, often accompanying a hero of some kind, and is usually represented in an ordinary way beyond the fanciful or fantastic.

In popular belief the dog is considered to bring luck, beside the all-black dog which causes financial trouble, a white dog with a black head brings fortune to its master while a white dog with a black tail brings honor. In traditional mythology both mortals and immortals in heaven keep dogs, like the legendary Er-Lang deity, Yang Jian, whose buck always helped him to defeat demons and monsters. The heavenly Tiangou (天狗) is probably the most famous dog, and a good spirit that brings peace and protection when white-headed is, but which in the form of a black dog is a bad character capable to eat the moon. As we understand the dog is a powerful pop icon and signifier in Chinese myth with multiple significations and distinct appearances.

If the dog carries a significant meaning in Chinese culture, tradition and thought, so do the beggar, which as a motif in literature and painting, is closely associated to ghosts and demons, as a bridge between two worlds. In “Lamentation for the Liumin” (Ai liumin cao 哀流民操) the famous sanqu 散曲 poet and official Zhang Yanghao 張養浩 (1269-1329) wrote: “Alas, the liumin! They are ghosts, they are not; they are human beings, they are not”. (哀哉流民 為鬼非鬼,為人非人). Traditionally ghosts, demons and other dissatisfied spirits were seen as the supernatural equivalent of beggars, and for Chinese poets and painters alike beggars evoked the world of bony hungry ghosts (餓鬼). Like in Zhou Chens (c.1450-c. 1536) renown painting Beggars and Street Characters (1516), which depicted skeleton-thin limbs and swollen bellies in almost ghostly forms. Yet the imagined physical similarities between the beggar and the ghost brought other connections, where beggars were considered during the Ming and Qing dynasties to be “mean” people (賤民), in contrast to ordinary commoners (良民), viewed as outsiders, always potentially dangerous, challenging social systems and political orders.

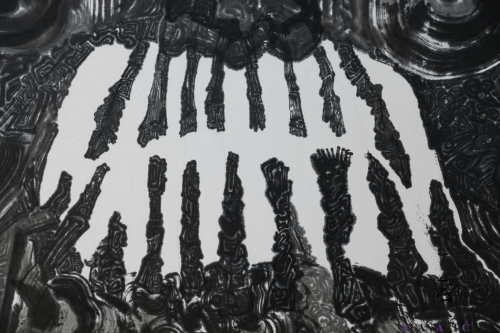

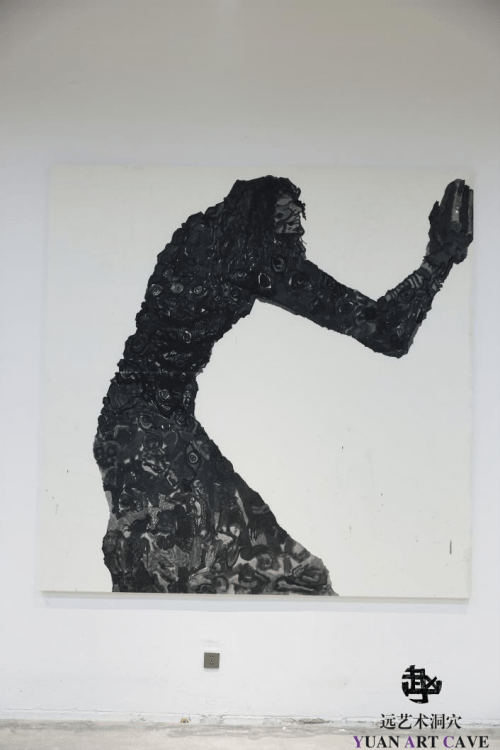

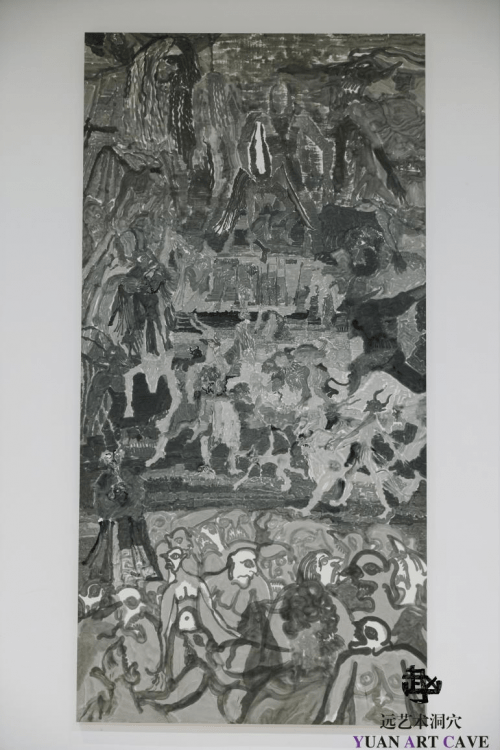

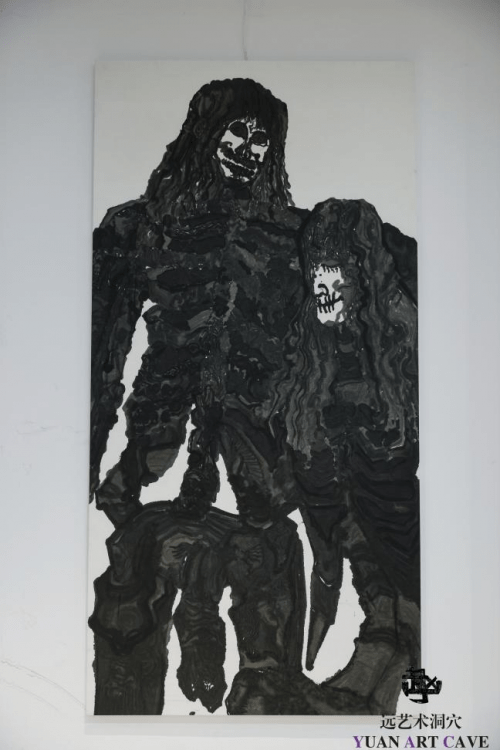

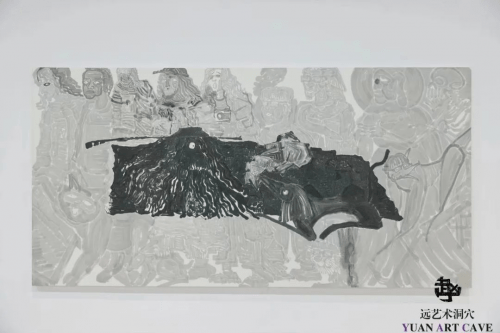

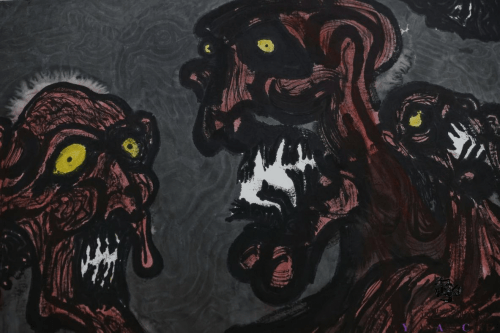

If the dog and the beggar as motifs of mythology permeats Zhao Ming Yuan’s paintings with a depth that frames their contemporary signification and personal symbolism, the ancient pop iconography directs it towards narratives that are also inherent in other motifs. From self-portraits, to evocative memento mori death skulls and skeletons reminding us of our mortality and the brief fragility of human life. A theme dating back to the Renaissance of a Hans Holbein as well as to a contemporary artist like Damien Hirst. In a similar vein Zhao Ming Yuan depicts mythological motifs of a diabolic Lucifer figure with two horns, demon eyes, grimacing mouth, large sharp protruding teeths and claw-like feet and hands. A mythological reference that recalls the German Krampus legend depicted by Joseph Beuys, or those articulated in the Last Judgement iconography of Giotto, Michelangelo and Hieronymus Bosch. All of whom were inspired by the famous Italian poet Dante Alighieri and The Divine Comedy: Inferno (c. 1308-1321), which since its publication has served as a crucial touchstone for artists and philosopher imagining hell, influencing even todays comic book and computer game designers. A universal mythology which of course also finds its correspondence in the Chinese Diyu and its 18 level of purgatory, or for that matter to the Buddhist demon Matra and other horn wearing deities.

Zhao Mingyuan special relationship to animals began at an early age when he had a crab as a beloved pet, it was followed by a fish and a cat. He shows a keen interest to distinguish details, and depict small animals with a refined and vivid brushwork which for a young painter like himself is a most important point. Echoing the metaphoric articulation of Zhu Da (1626–1705 ) known as Bada Shanren who expressed his inner vision of the external world and of human affairs by painting landscapes, Zhao Mingyuan employs in a similar manner animals as metaphors. Merging a Chinese traditional perspective with a contemporary vocabulary, exmplified in his painting-assemblage, where a carp fish painted in ink on paper a classical style is inserted into a used and broken wooden window frame featuring a real plastic net. With the representation of the fish caught in all its symbolism of prosperity, abundance, luck, and happiness. Zhao Mingyuan employs in general the traditional Chinese concept of the unity of nature and man, in which details are metaphors for larger issues, merging a classic Chinese form with a contemporary vocabulary, while using a universal symbolism with a shifting micro and macro perspective.

If Zhao Ming Yuan explores a varied world of motifs, he does so with a rare pictorial sensibility ranging from a much refined calligraphic form and sensual brushwork, to a raw archaic expressionism. Articulating a creative purity and directness through a sensible palette of forms and imaginative intuition. Working in the Chinese painting tradition of ink-water-paper, his style is diversified yet follows his own personal emotional flow of being, in symbol and expression, from love, death, happiness, desperation or sadness. Emotions, with which we all can identify. His work is replete with symbolic narratives, whether it is an eye filled figure kneeling in prayer, a woman embracing a man while stabbing him with a knife, a standing man satiated with portrait-phases of his own life cycle, or just a beggar quietly smoking his pipe, a staring dog with large eyes, a smiling demon, or a crying man, Zhao Ming Yuan formulates an imagination of the personal, both surprising and astounding. Images that refers to reality, legend and literature, proclaiming the importance of an independent vision, through an expressionist resistance to the formats of the mainstream. Reclaiming the void which we all can feel at times, the emptiness embodied in the white paper and silence, filling this spiritual underground with emotions and life of pure being and future potential.